House Holds Hearing On 'Deepfakes' And Artificial Intelligence Amid National Security Concerns

The House Intelligence Committee heard from experts on the threats that so-called "deep fake" videos and other types of artificial intelligence-generated synthetic data pose to the U.S. election system and national security at large.Friday, June 14th 2019, 4:34 am

The House Intelligence Committee heard from experts on the threats that so-called "deep fake" videos and other types of artificial intelligence-generated synthetic data pose to the U.S. election system and national security at large. Witnesses at Thursday's hearing included professors from the University of Maryland, University at Buffalo and other experts on AI and digital policy.

In a statement, the committee says it aims to "examine the national security threats posed by AI-enabled fake content, what can be done to detect and combat it, and what role the public sector, the private sector, and society as a whole should play to counter a potentially grim, 'post-truth' future," during Thursday's hearing.

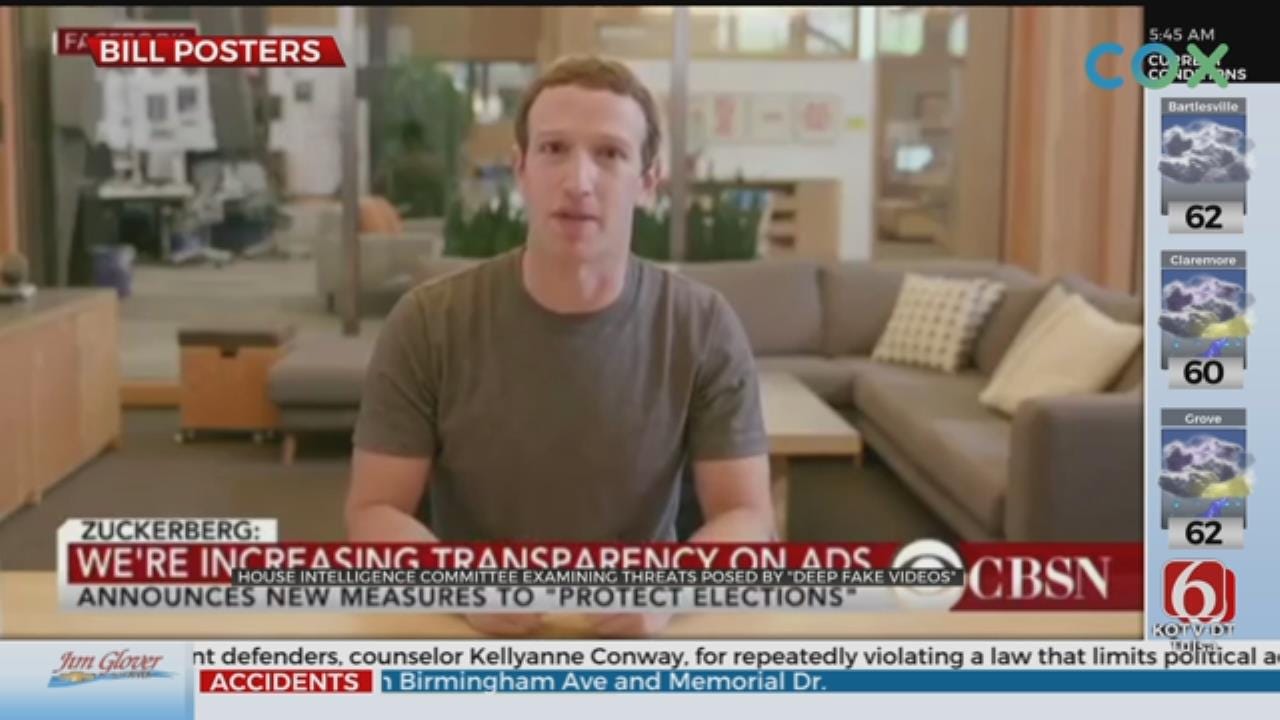

The hearing comes amid a growing trend of internet videos showing high-profile figures appearing to say things they've never said.

Recently, a doctored video of House Speaker Nancy Pelosi, in which she appears to be impaired, made the rounds on social media. The video garnered more than 2.5 million views on Facebook after President Trump shared it in an attempt to make light of Pelosi's speech patterns and fitness for office. Republicans and Democrats are now concerned these manipulated videos will become the latest weapon in disinformation wars against the United States and other Western democracies.

"Deep fakes raise profound questions about national security and democratic governance, with individuals and voters no longer able to trust their own eyes or ears when assessing the authenticity of what they see on their screens," the committee said in a statement.

In his opening remarks, Committee chair Rep. Adam Schiff said the spread of manipulated videos presents a "nightmarish" scenario for the 2020 presidential elections -- leaving lawmakers, members of the news media and public "struggling to discern what is real and what is fake."

Schiff urged that "now is the time for social media companies to put in place policies to protect users from misinformation, not in 2021 after viral deepfakes have polluted the 2020 elections. By then, it will be too late."

Highlights from the hearing:

Expert: No "silver bullet" to defeating deepfakes

Danielle Citron, Professor of Law at the University of Maryland Francis King Carey School of Law, testified that there's no finite way to stop deepfakes from spreading, but said a combination of "law, markets and societal resiliences" are necessary to get resolution.

"But law has a modest role to play," Citron conceded. She explained that victims in civil claims can sue for defamation or emotional distress from the videos, but added that it's "incredibly expensive to sue and criminal law offers too few levers for us to push."

Experts offer "dangerous" hypotheticals

"We tend to believe what our eyes and ears are telling us...video is visceral ..the more salacious it is, we're more willing to pass it on. The whole enterprise is to click and share," Citron testified. She offered several hypothetical situations where deepfakes can be used in damaging ways, including in pornographic materials and in Initial public offerings.

"The night before a public offering... a deepfake showing a company's CEO...could upend the IPO, the market will respond and fall far faster than we can debunk it," she suggested.

Expert says lawmakers should work with social media companies

Clint Watts of the Foreign Policy Research Institute said that politicians need to work to "rapidly refute smears" that are presented in any deepfake videos shared online. He noted that can be done in a "partnership" with social media companies. Watts also suggested that the government continues its efforts to impose strict sanctions around troll farms, similarly in the wake of the 2016 Russian interference campaign.

"What we did see if we look at the GRU indictment, they're essentially being sanctioned and outed," said Watts. He suggested that hackers and companies involved in troll farms don't want to be hired at those targeted firms after being indicted by the U.S. government. Sanctions, in effect, have helped turn down employment at those respective firms.

Expert warns of dangers of "instantaneous" nature of deepfakes

"A lie can go halfway around the world before the truth can get its shoes on, and that's true," David Doermann, Professor, SUNY Empire Innovation and Director, Artificial Intelligence Institute at the University at Buffalo testified.

"Personally I don't see any reason why, news does it with live types of delays, there's no reason why things have to be instantaneous, social media should instill these kinds of things to delay," he suggested. Doermann went on, saying there are tools the social media companies could use to link verifiable audio and video together and make a decision regarding pulling it down from their respective sites "the same way we do with malware or cyber issues."

"We're protecting our front door," he said.

What can 2020 campaigns do about deepfakes?

Experts testified that presidential hopefuls and their respective campaigns need to work hand-in-hand with social emdia companies to create "unified standards" on misinformation.

"Pressuring industry to work together on extremism, disinformation…rapid responses to deal with this stuff. Any sort of lag in terms of a response allows that conspiracy to grow, the quicker you get out on it the better and mainstream outlets and other officials can help," Watts maintained.

Citron agreed, saying campaigns need to make a "commitment" not to spread or share deepfakes over the course of the campaign and build better relationships with social media companies in order to directly refute any misinformation online.

She said consumers and voters need to learn to be "skeptical without being nihilistic."

Longterm "corrosive" effects of deepfakes, disinformation

Experts all agreed that the use of deepfakes has serious implications on society, not just politics -- namely journalism. Jack Clark, Policy Director at OpenAI called it an "undercover threat" to news media as manipulations look to convince the public that reporting is factually inaccurate.

Citron agreed, saying that deepfakes that are tough to debunk can potentially lead journalists to sit on evidence or reporting for fear that it's fake. She called that "corrosive effort by online trolls a "truth decay" that impacts everything, including journalism and the media.

Watts meanwhile warned that overtime, the use of disinformation and deepfakes could lead to "longterm apathy."

"If overtime they can't tell fact from fiction, they'll believe everything or nothing at all," said Watts. He pointed to the relationship between the Russian government and its people, saying the Kremlin uses a "firehose of falsehoods" to control public opinion.

Reporting by Emily Tillett and Olivia Gazis

More Like This

June 14th, 2019

September 29th, 2024

September 17th, 2024

Top Headlines

November 22nd, 2024

November 22nd, 2024

November 22nd, 2024

November 22nd, 2024