Telling The Story Of The 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre Through Artifacts, Historical Documents

Containing more than 36,000 artifacts, the Smithsonian's National Museum of African American History and Culture (NMAAHC) documents every aspect of African American life, history, and culture. Among the artifacts are a select few on the museum's third floor that help tell the story of the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre and its aftermath.Thursday, May 27th 2021, 10:41 am

Washington, D.C. -

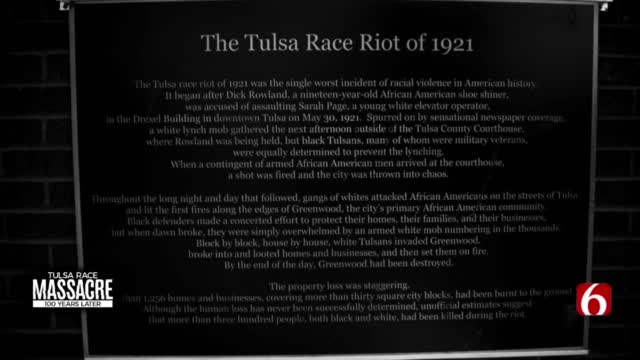

Containing more than 36,000 artifacts, the Smithsonian's National Museum of African American History and Culture (NMAAHC) documents every aspect of African American life, history, and culture.

Among the artifacts are a select few on the museum's third floor that help tell the story of the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre and its aftermath.

"What we are trying to show in this particular gallery, called the Power of Place," said Smithsonian Emeritus Curator John W. Franklin, "is the range of African American experiences in the nation over place and time."

John Whittington Franklin is not a native Tulsan, but his family ties have given him a deep and unique understanding of the African American experience there.

His grandfather was B.C. Franklin, an attorney whose Greenwood office was among the dozens of businesses destroyed. His written account provides one of the most detailed descriptions of the assault ("From my office window I could see planes circling in midair. They grew in number and hung and darted and dipped below. I could see the old Midway Hotel on fire burning from the top, and then another and another and another.")

And when Tulsa city leaders demanded that new buildings needed to be built with fire retardant material, it was B.C. Franklin who challenged the requirement in the Oklahoma Supreme Court and won, making it possible for Black businesses to rebuild.

John W. Franklin's father -- B.C.'s son -- John Hope Franklin, grew up in Tulsa, attended Fisk University, earned a PhD from Harvard and became a world-renowned expert on racism, historian and author.

The youngest Franklin attended Stanford, worked for decades for the Smithsonian and played a major role in creating the Race Massacre exhibit at NMAAHC, which opened in 2016. He was convinced it could serve as a powerful example of both racial injustice and of resilience.

"I began to lobby very early," Franklin recalled during a recent interview at his home, "that Tulsa is one of the stories we needed to bring to attention at the national level."

"And the two of us traveled together to Tulsa for the better part of six years," said Paul Gardullo, Supervisory Museum Curator and Director for Center for the Study of Global Slavery.

In the years leading up the museum's opening, Gardullo and Franklin were a team, inspired in their mission to curate the Tulsa exhibit by something Franklin's father told them.

"He said that the most important thing we could do," Gardullo recalled during an interview, "is to tell the unvarnished truth about our past."

No artifacts in the exhibit are perhaps more unvarnished than five scorched pennies collected in the ruins of Greenwood by George Monroe, who was age 5 at the time of the massacre. Monroe kept those and other coins he found as personal treasure for decades, but then, Gardullo says, as he began to tell people the story of the massacre, he would gift the coins as tokens of trust.

"And we display them as relics," Gardullo explained, "we display them as evidence, we display them in honor of Mr. Monroe and the enormous trust he placed in people carrying the story forward."

Likewise, Gardullo says he and Franklin had to earn the trust of Tulsans as they sought the artifacts and photos that would allow them to tell such a powerful and multi-faceted story.

"We found a panorama of the destruction of Greenwood and we used it to wrap three walls of the gallery where we tell the history of Greenwood," Franklin said, "and you can see not only the devastation, the burnt trees, the rubbles of the businesses and homes, but you can see tents where people have pitched tents to begin rebuilding and begin to reclaim the land that they thought they were going to lose."

Of course, there are numerous photographs in the gallery, but perhaps none more chilling than the ones that were turned into postcards.

"They were circulated locally and nationally," said Gardullo, "to help demonstrate what could happen if you became too successful and you were Black in America."

Many decades later, the postcards actually helped those arguing for reparations document the scope of the atrocities.

"They’re horrible," Gardullo said, "they're horrible, horrible things, but they can serve and have served a purpose of good."

A simple wooden chair tells another part of the history: the shame and guilt felt by many White Tulsans. Gardullo says a note on the chair when it was found at a consignment shop suggests it had been looted from a Black church.

"Yes, it's an object that was possibly taken from a Black church," noted Gardullo, "but it’s also an object that has come from the community as an act of perhaps restitution, as an act of perhaps reckoning."

Also included in the exhibit is a sampling of the oral histories -- video recordings of survivors' stories -- that have been collected over the years.

"The oral histories and the silent film footage also helped create a real image of what happened in Tulsa," Franklin stated, "beyond just still photographs and artifacts and made it more riveting as an experience."

Gardullo and Franklin say the Tulsa experience is relevant in the nation's current debate over race, because the unvarnished -- and until recently, untold -- truth of Tulsa, they say, is that not only is the African American community resilient, so, sadly, is racism.

"We have many hidden histories," Franklin said, "and I think that we can only grow as a nation if we learn what those histories are. Tulsa is one story."

"What our goal is," said Gardullo, "is to use history as a spark to help us deal with our present problems, and for me there’s no better example of that than Tulsa, Oklahoma."

After being shut down for more than a year due to the pandemic, the museum reopened May 14.

More Like This

May 27th, 2021

May 27th, 2021

May 27th, 2021

Top Headlines

April 15th, 2025

April 15th, 2025